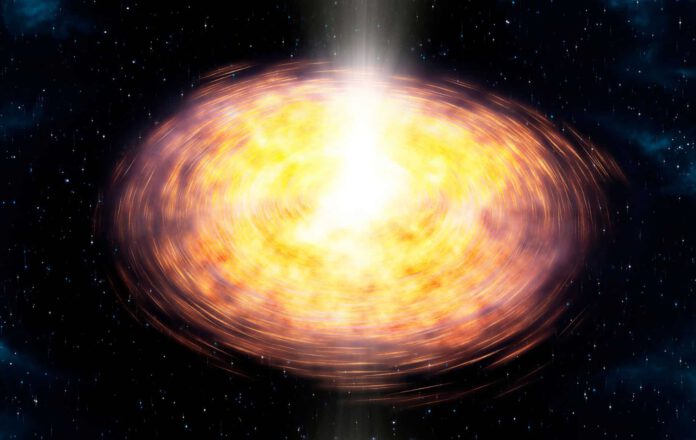

For a long time, it was suggested that icy ‘pebbles’ in the cold outer regions of protoplanetary disks form the basis for the creation of planets. That theory has now finally been confirmed.

How Planets are Born

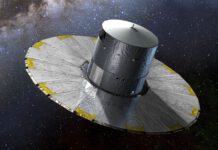

How do planets come into existence? It’s a pressing question that astronomers have been mulling over for some time. Fortunately, scientists have now developed a leading theory to explain this issue. Until recently, however, it had remained just a theory. Now, the James Webb Space Telescope has witnessed this process in action, finally establishing with certainty how planets are born.

The Theory

For a considerable period, theories have suggested that icy ‘pebbles’ in the cold outer parts of protoplanetary disks (the same region where comets in our solar system are formed) are the essential building blocks for the formation of planets. According to this line of thinking, these icy particles drift from the cold, outer areas of the disk towards the newborn star. The theory proposes that when these pebbles penetrate the warmer area closer to the star, they would release substantial amounts of cold water vapor, delivering both water and solids to developing planets.

James Webb

The crux of the matter is that the theory predicts that icy pebbles, upon entering the warmer area (where ice transitions into vapor), must release substantial quantities of cold water vapor. And that is precisely what the Webb telescope has now observed. By observing water vapor in protoplanetary disks, Webb confirmed that icy particles from the outer parts of protoplanetary disks drift to the rocky planet zone. A breakthrough. “Webb has finally shown how water vapor in the inner disk is associated with the drift of icy pebbles from the outer disk,” says research leader Andrea Banzatti. “This opens exciting possibilities for studying the formation of rocky planets using Webb.”

Study

The researchers made this discovery after studying four disks – two compact and two extended – around sun-like stars using Webb’s MIRI (Mid-Infrared Instrument). All four of these stars are estimated to be between two and three million years old, which is considered newborn in cosmic terms.

The goal of the Webb observations was to see if the compact disks have more water in their inner, rocky part. This would happen if the pebbles were delivered more efficiently, with a lot of mass and water. The team used MIRI’s MRS (Medium-Resolution Spectrometer) because this instrument is good at detecting water vapor.

Confirmed

The results confirmed what was expected. The researchers indeed found an excess of cold water in the compact disks. “It’s finally clear that there is an excess of colder water,” says Banzatti. “This is extraordinary and entirely due to Webb’s improved accuracy.”

Thanks to the study, published in the journal Astrophysical Journal Letters, we now finally know for sure how planets form. “In the past, we had a very static image of planet formation, almost as if there were isolated zones where planets were formed,” says researcher Colette Salyk. “We finally have evidence that these zones interact. And something similar probably happened in our own solar system.”