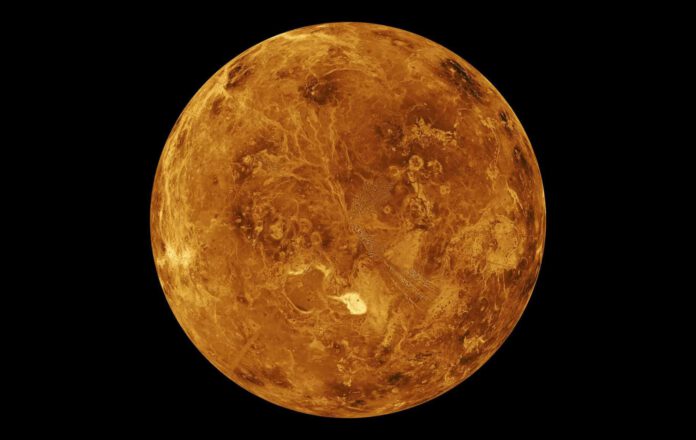

A new study suggests that Earth’s “twin sister,” Venus, may have had plate tectonics billions of years ago. This could have been potentially beneficial for microscopic life.

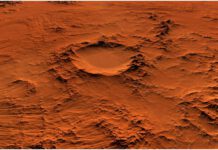

Venus, our closest planetary neighbour, is known to be a sizzling and inhospitable world. This is due to Venus’ severe greenhouse effect, where its dense atmosphere traps all heat, leading to surface temperatures that rise up to 465 degrees Celsius. Not exactly a suitable environment for life. However, researchers have discovered that Venus’s historical conditions might have been quite different, suggesting that it may have once experienced plate tectonics, similar to those of early Earth.

Twins

Venus shares many similarities with Earth, having comparable sizes and structures. However, conditions on Venus are notoriously harsher, from the intense heat to an atmosphere filled with corrosive sulfuric acid. Venus is therefore often described as the inhabitable twin sister of Earth. The big question is what led to the sharp diversion and stark difference between these twin planets. One theory proposed is that Venus possesses an ‘immobile crust,’ where its surface comprises a single massive plate with very little movement.

The Study

A recent study, however, suggests that this might not have always been the case. A group of scientists, reporting in the journal Nature Astronomy, analyzed data on Venus’s atmosphere and used computer models to draw conclusions. They concluded that the current atmospheric composition and surface pressure could only be the result of early plate tectonics.

Plate Tectonics

This finding is fascinating. Plate tectonics is a critical process for life formation, involving numerous continental plates colliding, pulling, and slipping under one another. On Earth, this process has continued to develop over billions of years, leading to the formation of new continents, mountains, and contributing to chemical reactions that stabilize surface temperature, ultimately fostering a more livable environment.

Meanwhile, on Venus

Currently, Venus’s atmosphere is rich in nitrogen and carbon dioxide. To account for this, researchers suggest that Venus must have had plate tectonics at some point between 4.5 and 3.5 billion years ago. The paper proposes that these ancient tectonic movements were similar to that on Earth, albeit with fewer plates moving less significantly. These movements took place around the same period on both Earth and Venus.

Similarities

This suggests that Venus might have more closely resembled Earth much more than we thought. “A key discovery is that both Earth and Venus likely had a similar process of plate tectonics at some point in time,” says researcher Matt Weller. “This process played a part in creating conditions that are favorable for life as we know it on Earth.”

Life

Indeed, this discovery implies that Venus could have once harbored life, potentially increasing the chance for the existence of microbial life on the planet.

Transition

The study also highlights the significance of the timing of plate tectonic activity on planets and its potential impact on the development of life. “Until now, we thought of plate tectonics as something very simple: it happens, or it doesn’t, and it remains that way throughout a planet’s lifespan,” states researcher Alexander Evans. The research suggests that planets might go through various tectonic phases, with Earth being a possible exception to this rule. Furthermore, it suggests that planets might be suitable for life at certain times but not others.

Atmosphere

All in all, the study implies that Venus and Earth, two planets of similar size, mass, density, and volume, and located in the same vicinity, may have been more akin to identical twins at one point. This provides intriguing questions about planetary evolution and the history of our solar system, all from studying Venus’s atmosphere. “Until now, we primarily considered a planet’s surface to decipher its historical record,” says Evans. “This research suggests that studying planetary atmospheres might prove more insightful in understanding their ancient history, even if it’s not well-preserved on the surface.”

In the coming years, the DAVINCI mission aims to confirm these findings by measuring gases in Venus’s atmosphere. In the meantime, researchers plan to further explore a significant question raised by the study: what happened to Venus’s plate tectonics? The team suspects that as the planet became hotter and its atmosphere denser, the necessary elements for tectonic movement eventually dried up. “In a sense, Venus exhausted itself, slowing down the process,” posits researcher Daniel Ibarra. The specific details of how this occurred on Venus could harbor profound implications for our own planet. “This marks the next crucial step in understanding Venus, its history and what it might signify for the future of Earth,” says Weller. “The biggest question now is: what conditions could cause Earth to follow a Venus-like path, and what conditions might keep our planet habitable?”