An Upcoming Extraordinary Event at Io

An event out of the ordinary is slated to happen at Io, one of Jupiter’s four large moons this Saturday. It marks the first time in two decades that a spacecraft will fly notably close to it, promising to yield captivating images.

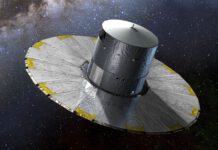

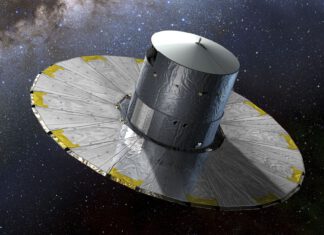

NASA’s Space Probe Juno

A day before the outgone year’s last, NASA’s space probe Juno will approach as close as 1,500 kilometers from the surface of Io—the largest volcanic world in our solar system. This is expected to yield a wealth of valuable data for researchers back on Earth.

“By blending data from this flight with earlier observations, scientists can research how Io’s volcanoes vary,” says the Juno’s chief researcher, Scott Bolton from Texas. “We aim to ascertain their eruption frequency, their light intensity, their heat levels, the shape changes of the lava stream, and how Io’s activity is connected with the flux of charged particles in Jupiter’s magnetosphere.”

Magma Ocean

The distance between the sun-powered Juno and the intriguing moon Io isn’t fixed. It once again approaches the captivating moon on February 3rd next year. Priorly, Juno was 11,000 to 100,000 kilometers away from the moon, delivering the first visuals of the moon’s North and South poles. Due to the moon’s surface, it is sometimes referred to as the ‘pizzamoon’. Moreover, Juno previously visited two of Jupiter’s ice moons, Ganymede, and Europa.

This time, however, the space probe is getting a tad closer as astronomers are eager to answer another major question. They want to discern the source of Io’s considerable volcanic activity: does a magma ocean lie beneath the moon’s surface, and to what extent do the tidal forces exerted by Jupiter, which apply immense pressure to Io matter? In addition, the space probe studying Jupiter for its third year will investigate the rings some of the moons are in.

Juno’s Three Cameras

Juno boasts three cameras, each working their hardest to properly capture everything during the flyby. The Jovian Infrared Auroral Mapper (JIRAM) captures infrared images to measure the heat emitted by the volcanoes and craters. The Stellar Reference Unit delivers images of the surface in the highest resolution to date. Finally, the JunoCam creates color images of visible light. Added for the benefit of the general public, it was originally intended for eight passes around Jupiter. However, the upcoming flyby with Io will be the 57th time Juno orbits Jupiter. So far, the spacecraft, with its cameras, has endured almost the most intense radiation in our entire solar system.

“The effects of all this radiation are beginning to be noticeable on the JunoCam”, says Ed Hirst, Juno project manager at NASA. “The photos from the last flight are of slightly lesser quality. Our technical team works to mitigate the radiation damage and keep the camera operating.”

Further Extension

As NASA researchers seem insatiable to learning, the mission is being extended further, adding seven extra flybys of Io. In total, Juno will fly by the volcanic moon eighteen times. Due to the gravity of Io during the visit on December 30th, the spacecraft’s orbit shortens from 38 to 35 days, and after the flyby on February 3rd, it will take just 33 days to orbit the gas giant.

The new route results in Jupiter blocking the sun for five minutes during the spacecraft’s closest approach. Although this is the first time the solar-powered spacecraft flies in the dark, since it flew by Earth in October 2013, the darkness is brief and does not negatively impact the spacecraft. Fortunately, until the end of the ride (late 2025), Juno will undergo such eclipses each time it approaches Jupiter.

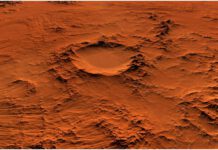

Pizzamoon Io

Io is blessed with more than four hundred volcanoes. It surpasses all celestial bodies in our solar system in terms of volcanic activity. The volcanoes spew out sulfur dioxide, resulting in the creation of its own atmosphere. A large part of this sulfur dioxide also ends up in space. The volcanic activity is brought about by the immense gravity of Jupiter, which creates friction and heat within Io. Furthermore, the two larger moons – Ganymede and Europa – heat up the insides of Io, thereby forming volcanoes on its surface.