The Tiny Moon Discovered Orbiting Asteroid Dinkinesh

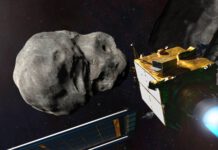

Last week, an intriguing discovery was made around asteroid Dinkinesh: a tiny moon. Surprisingly, this moon is now found to be composed of not one but two parts.

Space probe Lucy recently flew by asteroid 152830 Dinkinesh. The flyby confirmed what astronomers have suspected for some time – that the space rock is accompanied by a tiny moon. However, this is no ordinary moon, as new images are revealing. The natural satellite orbiting Dinkinesh is made up of two components.

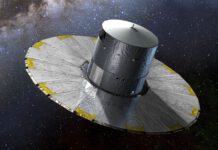

The Lucy Mission

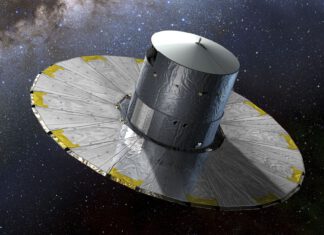

The Lucy space probe was launched just over two years ago. Its task over the course of the next decade is to visit various asteroids and so-called Trojans. These Trojans are remnants of the material from which the outer planets of our solar system were formed. By exploring these, researchers hope to gain more insight into the conditions that contributed to the formation of our solar system, over four billion years ago.

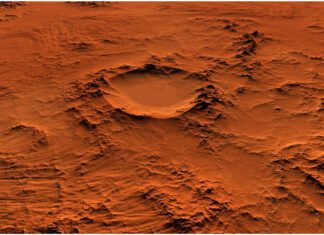

Last week, Lucy flew by her first target: 152830 Dinkinesh. This asteroid, with a modest diameter of 790 meters, was only discovered in 1999 due to its small size. This tiny space rock follows an elliptical orbit, meaning its distance to the sun varies from 290 million to 365 million kilometers. Dinkinesh is the smallest asteroid in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter that a spacecraft has ever visited.

The Moon

On the first returned images from Lucy, it was clear that Dinkinesh is accompanied by a small companion. But it turns out that there’s more than meets the eye regarding this asteroid and its newly discovered satellite. As more images continue to roll in, it’s now clear that the moon is what’s known as a ‘contact binary object.’ This means it’s made up of two smaller objects that make physical contact with each other.

Not One, But Two Pieces

So, the tiny moon of Dinkinesh is not made up of one but two parts. The reason astronomers are only now finding this out is understandable. In the first pictures, taken at the closest point of approach, the two parts of the moon were situated exactly behind each other from Lucy’s viewpoint. However, the probe fired off many more pictures in the minutes that followed. Only then did the true nature of the moon come to light.

Contact Binary Objects

The discovery that Dinkinesh’s moon is made up of two parts is remarkable but not entirely uncommon. “Contact binary objects are quite common in our solar system,” notes researcher John Spencer. “We haven’t often had the chance to study these objects up close, and it’s unprecedented to see one orbiting another asteroid. During the flyby of Dinkinesh, we noticed unusual brightness variations, which led us to suspect the asteroid had a moon. But we never expected anything this astonishing!”

A Mystery

This means that Dinkinesh consists not of one or two, but a total of three components. “This is puzzling to say the least,” says chief researcher Hal Levison. “I never thought a system could look like this. What I particularly don’t understand is why the two parts of the moon are of similar size. Unraveling this promises to be an exciting challenge for the scientific community.”

The Journey Continues

Meanwhile, Lucy continues her journey. Dinkinesh and her natural satellite mark the starting point of Lucy’s mission to investigate various interesting space rocks over a 12-year period. The probe will first head back towards Earth, before using a gravity slingshot to head for asteroid 52246 Donaldjohanson. From there, Lucy will proceed towards her main targets: the Trojans. If all goes according to plan, Lucy will be the first spacecraft to visit these ancient remnants of our solar system. The plan is to explore various Trojans between 2027 and 2033.

As Lucy heads towards her next destination, the team will continue to analyze the remaining data from the brief encounter with Dinkinesh. There is still plenty to unravel about this mysterious object. “It’s truly amazing when nature surprises us with a new mystery,” says team member Tom Statler. “Good science challenges us to ask questions we didn’t even know we needed to ask.”