Methane Mystery on Mars: What’s the Cause?

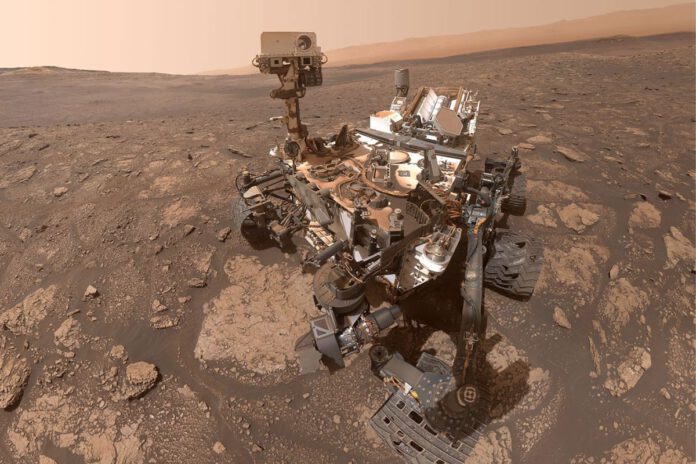

In 2019, NASA’s Mars rover, Curiosity, discovered methane on Mars. However, the reason for its existence and its unusual behavior remained a mystery. Now, we might have a clearer insight into this enigma.

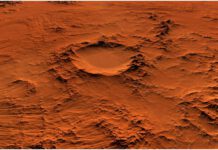

On Earth, almost all methane is produced by living beings, such as cows. Yet, as far as we know, Mars has little in the way of life, let alone enough to produce methane. Hence, it came as a shock to discover methane near the Gale Crater on the Red Planet, where Curiosity set foot over a decade ago. NASA researchers hypothesized that subterranean processes involving water and rocks could be releasing methane.

The Bizarre Behavior of Martian Methane

Yet, that’s not the end of the mystery. Curiosity revealed that the methane behaves strangely. It shows up at night and disappears by day. It also fluctuates with the seasons, soaring at times to levels 40 times higher than usual. Furthermore, unlike on Earth, the methane doesn’t accumulate in the atmosphere.

The Hypothesis

Scientists have been tirelessly searching for an explanation for both the methane’s peculiar behavior and its presence exclusively in the Gale Crater. Recently, they proposed an intriguing idea. It’s possible that the methane is trapped underneath hardened salt in Mars’ regolith – the ground composed of loose rocks, dust, and other detritus. When temperature rises during warmer seasons or specific times of day, the salt softens and methane might seep through.

Additionally, the gas might be released through cracks in the ground created by pressure from, for instance, a Mars rover. This could also account for why the gas has only been detected at the Gale Crater, one of the two places on Mars where rovers drill into the surface. The other location is the Jezero Crater, whose rover isn’t equipped to detect methane.

An Old Experiment Gives New Insight

The hypothesis takes its cue from a 2017 experiment in which scientists grew microorganisms in simulated Martian permafrost with added salt, replicating Mars’ actual conditions. The results were inconclusive, but they led to another discovery: the surface formed a salt crust because salt sublimates – changes from solid to gaseous state – leaving behind salt.

“We didn’t think much of it at the time,” says NASA’s Alexander Pavlov. But when Curiosity detected a methane burst in 2019 that nobody could explain, he and his team began testing conditions that could form and crack hard salt crusts. They added varied amounts of perchlorate, a commonly found salt on Mars, to the permafrost.

Varying Salt Concentrations

Today, there’s no permafrost left in the Gale Crater, but the salt crust might have formed long ago when it was colder and icier. The scientists exposed the samples to different temperatures and air pressure to observe what would happen. They periodically injected neon, a methane-analog, under the crust and measured the gas pressure above and below it. Higher pressure beneath the sample implied that the gas was trapped. And just as the researchers expected, a salt crust developed in three to thirteen days under Mars-like conditions, but only in the samples with 5 to 10 percent perchlorate.

That’s a much higher salt concentration than what Curiosity had measured in the Gale Crater. However, the soil there is rich in another type of salt mineral, sulfates. The researchers now plan to test whether sulfate can also form such salt crusts.

A Waiting Game for the Future

But along with these theoretical experiments, fieldwork is also necessary. Curiosity, however, only searches for methane specifically twice a year. The rest of the time, it’s busy drilling into Mars’ surface to analyze its chemical composition. “Methane experiments are very intensive, so we have to think carefully about when we want to conduct them,” commented one researcher.

The technology also needs further development. For instance, to test how often methane levels spike, we need a new generation of instruments that can measure methane continuously at multiple locations on Mars. “Part of the methane work is for future spacecraft more focused on answering these specific questions,” the researcher added.