Ice Giants Uranus and Neptune: A Shift in Colour Perception

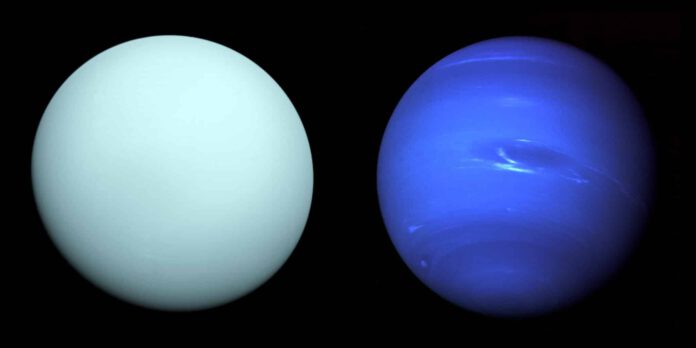

We’ve always thought of Neptune as blue and Uranus as light green. However, a recent study suggests that the two ice giants are almost the same colour: a shade of pale green.

Neptune is usually depicted as deep azure blue, while images of Uranus tend to show a very light green hue. Researchers from Oxford University have now demonstrated that both planets more or less share the same blue-green colour. This isn’t entirely a new revelation. Astronomers have long known that most images of the two planets don’t show their real colours. The misconception arose from post-processing of photos taken by NASA’s Voyager 2 in the 1980s, with Neptune especially being depicted too blue. Excessive contrast was also added to the photos to make the clouds, rings, and winds more visible.

“The well-known Voyager 2 images of Uranus were published in a colour close to its real colour, but those of Neptune were edited and enhanced, which made them artificially too blue,” explains Professor Patrick Irwin from Oxford. “Although this artificial colour was well-known among most planetary scientists at the time and the images were published with a caption explaining this, that colour difference has been forgotten over time.”

The researchers aimed to recreate the true colours by using data from the Hubble and the Multi Unit Spectroscopic Explorer (MUSE) from the ESO’s Very Large Telescope. Every pixel on these instruments contains a continuous spectrum of colours, allowing the actual colours of Uranus and Neptune to be determined. Eventually, it was found that they are almost the same colour, although Neptune remains slightly bluer.

Another Mystery Solved

Apart from ascertaining the true colour of these planets, the study also solved another intriguing issue—why Uranus’s colours appear to change during its 84-year orbit around the sun. Measurements show that Uranus seems a bit greener during the summer and winter solstice, when one of the poles of the planet points towards the sun. At the equinox – when the sun is directly above the equator – it has a slightly bluer tint.

The standard explanation for this is that Uranus spins on its axis in a very unusual way. During its orbit around the sun, the planet is almost on its side, which means that during the solstices the north or south pole points almost directly towards the sun and Earth. As a result, any change in the reflection of the polar region directly affects the overall brightness of Uranus, as viewed from our planet.

Methane Ice Particles

However, it was not previously clear how or why this reflection changes. The researchers developed a model that compares the spectra of Uranus’s polar regions with the region around the equator. This revealed something interesting: the polar regions reflect green and red wavelengths more than blue, partly because methane, which absorbs red, is half as prevalent at the poles as at the equator.

But this alone wasn’t enough to fully explain the colour change. So, the researchers added an increasingly thick ice layer to the poles, which had been observed earlier in summer, when the poles are illuminated by the sun as the planet moves from the equinox to the solstice. The layer is believed to be comprised of methane ice particles.

Simulations showed that the ice particles enhance the reflection of green and red wavelengths at the poles. This explains why Uranus appears greener during the solstice. “It’s due to a decrease in methane in the polar regions and also an increased thickness of bright methane ice particles,” says Irwin.

Time for a New Mission

It’s remarkable that a mystery which persisted for so long has now been solved. “The misconception about Neptune’s colour and Uranus’s unusual colour changes have puzzled us for decades, but this comprehensive study has resolved both issues”, says researcher Heidi Hammel from the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy (AURA), who has studied both planets for many years.

The ice giants Uranus and Neptune remain tempting destinations for future missions that can build upon the Voyager journeys of the 1980s. From the bizarre seasons to the vast number of rings and moons, there is still much to explore. But it’s not an easy task. Even long-lasting space probes can only catch a glimpse of a year on Uranus.