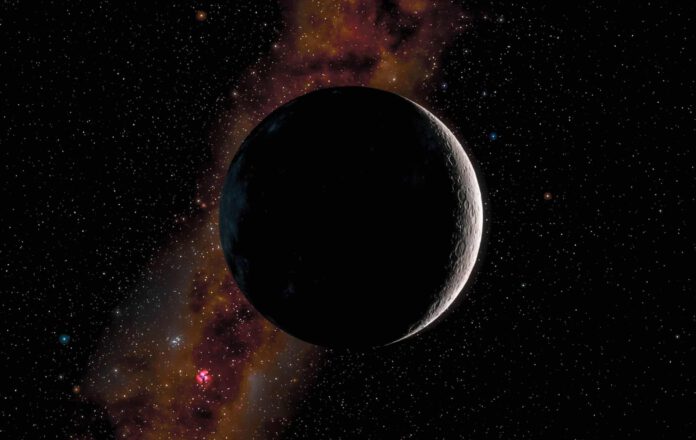

Exomoons, a promising field in the quest for life, yet, their discovery seems to be on hold, for now. In our solar system, it’s standard for planets to have one or more moons accompanying them. Every planet, except for Mercury and Venus, has such companions. Gas giant Saturn holds the crown with as many as 140 natural satellites! Therefore, scientists assume that planets in distant star systems likely also host moons. However, tentative evidence of this has only been found around the exoplanets Kepler-1625b and Kepler-1708b. A new study now casts doubt on these previous claims. “We would have loved to confirm the discovery of exomoons around Kepler-1625b and Kepler-1708b,” says the lead author of the new study, René Heller. “But sadly, our analyses show something different.”

Exomoons around Kepler-1625b and Kepler-1708b?

Five years ago, the Jupiter-like planet Kepler-1625b made big news. Scientists had found strong evidence of a massive moon in its orbit, which would surpass all moons in our solar system. Last year, this remarkable candidate exomoon got company: scientists believe there’s also a giant moon orbiting the Jupiter-like planet Kepler-1708b.

Overall, the exoplanets Kepler-1625b and Kepler-1708b are presumed to be the home worlds of the first known exomoons. However, a new study seems to debunk this exciting news.

Light Curves

“Exomoons are so far away that we cannot see them directly, even with the most powerful modern telescopes,” explains Heller. Instead, telescopes monitor the fluctuations in brightness of distant stars. This series of changes is called a light curve. Researchers then look for signs of moons in these light curves. When an exoplanet, as seen from Earth, passes in front of its star, it causes a slight eclipse of the star. This phenomenon, known as a transit, repeats regularly, synchronized with the planet’s orbital period around the star. If there’s an exomoon accompanying the planet, it would cause a similar eclipse effect.

Disappointing Results

In the new study, researchers used a newly developed computer algorithm, Pandora, which simplifies and accelerates the search for exomoons. However, instead of confirming the existence of exomoons around Kepler-1625b and Kepler-1708b, they come to a different, rather shocking discovery. The research team found that the observations for the planet Kepler-1708b can be explained equally well without the presence of a moon as with a moon. “The likelihood of a moon orbiting Kepler-1708b is significantly lower than originally thought,” says researcher Michael Hippke. “The data shows no evidence for the existence of an exomoon around Kepler-1708b.” Moreover, there’s strong evidence that Kepler-1625b likely doesn’t have a huge companion either.

False Positives

It means that the discovery of the very first exomoon is still impending. If that’s not disappointing enough, the new, comprehensive analyses also suggest that identifying an exomoon will be remarkably complex. Exomoon search algorithms often produce false positives. Time and again, the researchers ‘discovered’ a moon, where actually only a planet transits in front of its parent star. With a light curve like that of Kepler-1625b, the chances of ‘false positives’ are likely around 11 percent. “False-positive findings are not surprising but almost expected according to our estimates,” concludes Heller.

Exceptionally Large

The scientists also used their algorithm to predict what kind of exomoons can in principle be found using astronomical observations. According to their analysis, only exceptionally large moons orbiting their planet in a wide orbit are detectable with current technology. Compared to the known moons in our solar system, these exomoons would all be ‘oddities’: at least twice as large as Ganymede, the largest moon in our solar system.

The hunt for exomoons continues unabated. The idea that the very first exomoon discovered could be very unique may only serve to further fuel the scientists’ enthusiasm. “The very first exomoons that we will discover in the future will undoubtedly be extraordinary and therefore likely very exciting to explore,” Heller concludes.