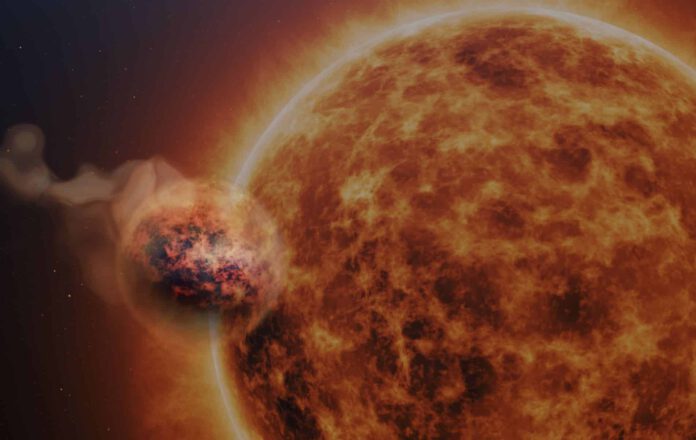

Scientists have discovered clouds in the atmosphere of the gas planet WASP-107b comprised of silicate, or essentially sand. Consequently, when it “rains” on this ‘fluffy’ gas planet, sand descends!

Clouds of Sand

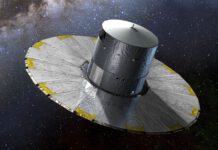

An international team of researchers reported this finding in the journal Nature, based on new observations from the James Webb Space Telescope, which peered deep into WASP-107b’s atmosphere. In addition to water vapour and sulphur dioxide, researchers found clouds of sand in the atmosphere.

Clouds have been detected on other planets, but this is the first time we’ve discovered their composition,” explains researcher Nicolas Crouzet. “In this case, the answer is silicate, or essentially, sand.”

The Candy Floss Planet

The fact that researchers were able to scrutinise the atmosphere of WASP-107b and characterise its clouds isn’t solely due to the James Webb Space Telescope’s ‘Mid-Infrared Instrument’ (MIRI), which was developed by an international team. The planet’s extremely low density also played a significant role. WASP-107b weighs about the same as Neptune, but it is substantially larger, nearly as large as Jupiter. This means WASP-107b has a much lower density than the gas giants in our solar system, earning it the nickname ‘fluffy planet’. This ‘fluffy’ characteristic of WASP-107b allows astronomers to look deeper into the planet’s atmosphere than would be possible on a planet like Jupiter. As a result of these studies, clouds of sand were discovered, which was rather unexpected. “We anticipated the existence of sand clouds and sand rains in the atmospheres of hot planets,” says head researcher Michiel Min. “But according to our predictions, WASP-107b should actually be too cold.”

The Mystery of Sand Clouds

On Earth, water evaporates at high temperatures. On hot gas planets, with temperatures around 1000 degrees Celsius, silicate particles evaporate, thereby forming sand clouds. However, in the outer regions of WASP-107b’s atmosphere, the temperature ‘only’ reaches about 500 degrees Celsius—too cold for silicate particles to evaporate. This implies that when a sand cloud rains out, the resulting sand rain can only re-evaporate deep inside the inner atmosphere, a depth the clouds would struggle to reach to form again. Yet, new sand clouds must be constantly formed on the planet, otherwise researchers wouldn’t have observed them. “The surprising fact we find them suggests the planet is surprisingly hot inside, preventing the clouds from sinking too deeply,” adds Min. In other words, underneath the relatively cool upper layer where we see the clouds, it must heat up rapidly enough to evaporate the sand rain and recreate clouds. “This is much like Earth’s water system.”

Lack of Methane

The idea that the temperature rises rapidly deeper into the atmosphere is further reinforced by researchers’ inability to detect methane in WASP-107b’s atmosphere. According to Min, “Methane is expected to be a key component of the atmosphere at lower temperatures, similar to Jupiter where methane is abundant. High internal temperatures destroy methane deep in the atmosphere.”

More Sand Clouds to Come

For now, WASP-107b goes down in history as the first planet on which sand clouds have been demonstrated. However, Min anticipates that similar clouds will be discovered on more planets. “Especially on hotter planets. I hope that with detailed measurements, we can say more about the type of sand (the precise composition) we’re going to find under which conditions. This will teach us a lot about the cloud formation process.”

In addition to discovering sand clouds, the MIRI instrument will likely reveal other exotic weather systems. “The fact that we are now finding the predicted sand clouds shows that the cloud formation system is common,” Min explains. “On slightly colder planets, we might see clouds of various salts. And on planets with a more carbon-rich composition, perhaps graphite or diamond rains.”