With the help of the James Webb Space Telescope, researchers are able to reconfirm that the Hubble Telescope correctly estimated the rate at which the universe is expanding. And this is a problem.

For some time now, it has been known that Hubble’s measurements do not match those of other observatories. Consequently, there was an expectation or perhaps even hope that there were errors in Hubble’s estimates leading to the observed and unexplained discrepancy between Hubble’s observations and those of other observatories. However, Webb now confirms that Hubble’s measurements are accurate. This strongly hints that the universe is differently structured than previously thought.

The Beginning

When the Hubble Space Telescope was launched in 1992, scientists had numerous big plans for it. One of them was to definitively determine the rate at which the universe was expanding. Attempts to establish this using earth-based telescopes were somewhat disappointing, as the measurements were plagued by significant uncertainties leading to a wide range of estimates. Some telescopes suggested a rapid expansion and therefore a relatively young age for the universe (around 10 billion years). A fast expanding universe implies a younger age since galaxies need less time to reach their current vast distance from each other. Meanwhile, other telescopes suggested a slower expansion of the universe and a much older age (around 20 billion years).

Hubble

The keen eye of Hubble was hoped to remove these uncertainties and reveal the real rate of the universe’s expansion. Indeed, in the past 34 years, Hubble has given us a much more accurate picture of the rate at which the universe is expanding and hence the age of the universe. Hubble’s observations suggest that the universe is expanding at a speed of about 73 kilometers per second per megaparsec. This implies that the universe is about 13.8 billion years old.

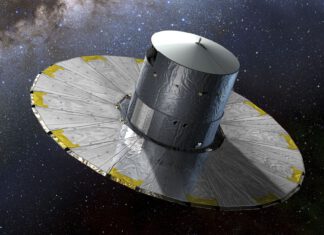

Planck

All seemed well until ESA’s Planck satellite entered the picture. Using this satellite, researchers measured the cosmic background radiation (see box). According to Planck’s measurements, the universe is expanding at a speed of about 67 kilometers per second per megaparsec. That’s a significant difference from the Hubble measurements. And no matter how often the researchers redid their calculations, that difference persisted. This drove cosmologists to despair as they were unable to explain why Hubble’s measurements differ so much from those of Planck.

Possible Error?

At least officially, scientists couldn’t explain this. Unofficially, they of course had ideas. The most obvious idea was that Hubble’s measurements weren’t entirely accurate. Especially as Hubble looked deeper into the universe and thus further back in time, its readings would become less reliable, some researchers suspected. This is due to the fact that Hubble looks at individual stars to calculate the universe’s rate of expansion, specifically cepheids.

Hubble can distinguish individual cepheids in galaxies located more than a hundred million light years away and measure the period of their brightness changes. This makes the telescope well suited for investigating the expansion of the nearby universe. But when researchers noted the discrepancy between the results of Hubble and Planck, which examines the universe’s expansion shortly after the Big Bang, they began to doubt. They suggested that Hubble’s measurements might be wrong, speculating that the telescope might be more affected by dust between us and distant cepheids than previously thought, which would make the pulsating stars appear fainter to Hubble than they truly are thereby misestimating the distance.

James Webb

To examine this, researchers have now deployed the James Webb Space Telescope. This infrared telescope is not affected by dust and can easily separate the light of cepheids from that of neighboring stars with its large mirror and sensitive optics. For the study, scientists let the telescope observe several galaxies that altogether housed about 1000 cepheids, including the farthest galaxy in which a cepheid has been measured. And each time, the researchers could draw the same conclusion: Webb’s observations underscored the expansion rate previously determined based on Hubble’s observations.

The new study, published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, follows a similar study published last year. In that earlier study, Webb examined relatively nearby cepheids that Hubble had previously measured. It was already shown then that Hubble’s measurements were accurate. But the suspicion that errors might have crept into Hubble’s measurements as it began looking at cepheids further away from us persisted. With this new study, in which James Webb once again measured those more distant cepheids, that suspicion seems to have been dismissed. The so-called Hubble tension remains. “With measurement errors ruled out, only the exciting possibility that we misunderstood the universe remains,” said researcher Adam Riess.

Current Status

So for now, we have Hubble’s measurements, conducted in the nearby universe, on one hand. And Planck’s measurements, which provide more insight into the expansion shortly after the Big Bang, on the other hand. And both appear to be correct but do not agree. This suggests that the expansion rate changed somewhere in the billions of years between the origins of the cosmic background radiation and the creation of the cepheids that both Hubble and Webb have observed. But how can that be? “It could point to the presence of exotic dark energy, exotic dark matter, a revision of our understanding of gravity, or the presence of a unique particle,” researchers speculated as far back as 2023. But for now, it’s just speculation. Perhaps other observatories, such as NASA’s under-construction Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope or ESA’s recently launched Euclid mission, will be able to provide more clarity in the future. “We need to figure out if we’re missing something,” says Riess.